Documentation sheet, Documentation Centre on the Vlaamse Rand, 2010

Introduction

The Egmont Pact, or the Egmont Agreement, complemented by the Stuyvenberg Agreements, constitutes the so-called Community Pact that was aimed at finally laying to rest conflicts that had arisen among the linguistic communities in Belgium. The Egmont Pact was the outcome of a compromise that had been signed on 24 May 1977 at the Egmont Palace by the then PM Leo Tindemans, his Chief of Cabinet, Jan Grauls, and the coalition party chairmen of the Christian Democrats (CVP-PSC), the Socialists (BSP-PSB), the Flemish Regionalist Party (VU), and the Democratic Front of the Francophones (FDF). During the Stuyvenberg negotiations (17-23 February, 1978), the Egmont Pact was partially adapted.

Situation

This historic pact between the Flemish, Walloon, and Brussels Regions was ultimately not put into practice, strongly opposed as it was by forces both within and outside the coalition parties, heavily criticized by the Council of State on a number of pillars in the agreement, hampered by the divergent interpretations placed upon the pact by the Dutch-speaking and French-speaking factions, the internal tensions fomenting within the parties themselves, and the difficulties associated with the actual implementing procedure. On 11 October, 1978, PM Tindemans stated in Parliament that, as far as he was concerned ''the Constitution is not just a scrap of paper'' and subsequently submitted the resignation of his government, thus sounding the final death knell for the Community Pact. Nonetheless, some of the Pact’s important elements were adopted in subsequent Belgian constitutional reforms; others are being resorted to whenever a compromise is sought to resolve community deadlocks.

The Pact comprised telling state reforms, with greater autonomy for the three communities – with their own councils and government bodies entitled to issue decrees – and the creation of 3 Regions, likewise with their own individual councils and government bodies that could issue edicts, in other words, the basis of the present federal state institutions. The communities received the competence de adtributis personae (e.g., issues relating to the individual); the regions de adtributis loci (e.g., matters relating to location) – a concept that, likewise, would later effectively be implemented in a subsequent state reform.

Less known is the fact that the Egmont Pact also foresaw in the elimination of the provincial political structures, these to be replaced with 25 sub-regions and the reform of both Parliament and Senate. The Brussels Region remained restricted to the 19 municipalities while the members of the Brussels Regional Council would be elected from unilingual lists. Governance by consensus and the alarm bell procedure were two other measures to counter discrimination versus Dutch speakers in Brussels. In the Brussels communities and in the 6 Belgian municipalities with language facilities for speakers of the minority language, Municipal Community Committees would be formed for the purpose of letting the communities themselves deal with the said person-related issues.In this manner, the French Community Council was given the opportunity to provide subsidies to socio-cultural activities in the municipalities with language facilities for speakers of the minority language. Also other guarantees for Dutch speakers in Brussels were coupled to the situation of the Francophones in the 6 peripheries.The administrative custodial supervision over these 6 districts was placed under the competence of the Minister of the Interior. The Community Pact also provided in an agreement about splitting the electoral district Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde, whereby a seat distribution between the Flemish lists from Halle-Vilvoorde with those from Louvain was arranged for.

Inscription Right

To regularize the relationships between Brussels and the peripheral districts, recourse was taken to the inscription right for Francophones in a Brussels municipality as counter-weight to the guarantees for the Flemish population within the capital.

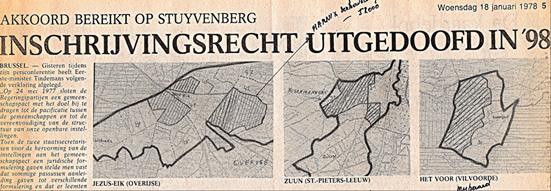

This inscription right was in effect in the 6 municipalities with language facilities for speakers of the minority language and within the so-called Egmont municipalities, Alsemberg, Beersel, Dilbeek, Groot-Bijgaarden, Sterrebeek, Sint-Stevens-Woluwe, Strombeek-Bever, and in the districts ’t Voor (Vilvoorde), Jezus-Eik (Overijse), and Zuun (Ruisbroek). Francophones from those municipalities were allowed notional inscription in a Brussels municipality, thus becoming eligible for certain language facilities and the right to vote for candidates from the Brussels region. The Stuyvenberg Agreement ensured that within the said municipalities with language facilities for speakers of the minority language the inscription right remained of indefinite duration, while in the other municipalities it was limited to 20 years, in other words, until 1998. The inscription right further made it possible for French-speaking children from the Egmont municipalities to be enrolled in kindergarten and primary schools within the afore-mentioned 6 municipalities with language facilities. This compromise encountered strong resistance from the Flemish side. As had been the case for the facility arrangement in the language compromise arrived at during the meetings in the Castle of Val Duchesse, it was in this instance also specifically the arrangement pertaining to the peripheral districts that was found unacceptable by the Flemish side. The resulting discontent found its main voice in the Anti-Egmont Committee, which organized numerous campaigns and demonstrations, among them the protest of 23 October 1977 in Dilbeek. A number of municipal councils likewise joined the protest campaign started under the slogan Where the Flemish are at home.

This strong resistance was also fuelled by the divergent interpretations between Flemish and French speakers of certain points in the agreement and the unbridled comments about them in the media. The increasing tensions arising among the leaders of the coalition parties and the presidents of the factions that had negotiated the pact in their turn cast serious doubts about the viability of the compromise. Within the CVP party, great divisiveness reigned, but similarly in other Flemish parties, the Pact led to schisms. The final outcome of this matter finally resolved into a serious political crisis within the parties, resulting in the end in radical break-aways within the Flemish Regionalist Party and a community fracturing within the last Unitarian party in Belgium, the Socialist Party.

Our database contains many more documents. Most of them are only available in Dutch. However, you can enter English search terms.