Documentatiecentrum Vlaamse Rand, Rand-ABC-fiche, april 2013

In Belgium, a number of institutions were created in order to pacify the relations between the language communities. Language legislation, drawn up following Community negotiations, indeed left room for further interpretations. In order to resolve disputes resulting from such inconsistencies, the advisory opinion of the Standing Commission for Linguistic Supervision (SCLS) applies. Moreover, in the Brussels municipalities, a Vice-Governor for Brussels Capital monitors the application of language legislation. Complaints or violations in the six peripheral municipalities are dealt with by the Deputy-Governor of the Province of Flemish Brabant.

The Standing Commission for Linguistic Supervision is an advisory body to monitor strict compliance with language legislation. In case of a complaint or violation with a public service (federal, Communities, Regions, provinces, municipalities or similar administrations), the SCLS can instigate an investigation and formulate an advisory opinion. These advisory opinions have no binding force. Private individuals may lodge a complaint with the SCLS (by registered post addressed to the chairperson), and Ministers as well are supposed to call on the SCLS for advisory opinions about language legislation in case of relevant initiatives. The Standing Commission also supervises language examinations provided for in language law.1

Activities

The Commission is composed of a Dutch-language division and a French-language division, which gather in a Joint Assembly. The divisions are competent for matters relating to their language area in municipalities without a special regulation. The Joint Assembly deals with matters that concern the Brussels municipalities, the municipalities with linguistic facilities or the German language area or that exceed the language legislation, such as the protection of minorities. There are a number of differences in powers, according to the applicable regulations in the respective language areas. For instance, the Dutch-language division also monitors compliance with the 19 juli 1973 Flemish Parliament Act 'regulating the language use in the social relations between employers and their personnel, as well as the instruments and documents of enterprises that are required by law and regulations'. The SCLS is composed of a (bilingual) chairperson and 11 members, each appointed for a period of 4 years. The candidate-members are nominated by the Councils of the Flemish, the Walloon and the German Communities and the president of the Chamber of Representatives.

The Joint Assembly

The Joint Assembly deals with issues that are not related to language homogeneous areas. It is composed of 5 Dutch-speaking and 5 French-speaking members, completed with a German-speaking committee member which is only consulted when municipalities from the German language area or the region of Malmedy are involved. Given the parity, the legislator also provided a regulation in case the commission members do not come to an understanding about a certain complaint. If no advisory opinion could be formulated 180 days after filing a complaint, the Minister for Home Affairs can take responsibility for issuing an advisory opinion within 30 days. The exceeding of the term does not, however, exempt the SCLS from the competence to deal with the complaint. In other words, the complaint does not expire once the term of 180 days has ended. The decisions of the SCLS are issued as advisory opinions, as a result of which the authorities concerned kept the final decision-making power and could, as a consequence, also disregard the advisory opinions. The advisory opinions often concern interpretations of vague or unclear stipulations in language legislation, which cause fundamental disagreement between the communities at political level.

Background

In order to enforce compliance with language laws, the Standing Commission was established in 1932, consisting of 6 members who were appointed by the King for a period of 4 years. They were elected from the members of the Vlaamse en Franse Koninklijke Academie voor Taal en Letterkunde (Flemish and French Royal Academy for Language and Literature). This new body was supposed to monitor the strict compliance with the language laws in the administration, courts and education, but had a merely advisory competence. This commission could only take action after a complaint had been filed. This complaint was then submitted to the Government, together with the advisory opinion, with a view to a solution. As a result of the onerous procedure and the lack of sanctioning powers, the door was left open to all kinds of violations. The higher administrations were indeed dominated by French-speaking persons who often considered the language laws as unwanted interference from above.

Hertoginnedal and St. Michael's Agreement

On 23 March 1964 the Standing Commission for Linguistic Supervision was established again. As it appeared, compliance with the language laws could not be enforced without vigorous control mechanisms. The competences of the SCLS were extended by provisions in the St. Michael's Agreement. It evolved from a merely advisory body into a body that, theoretically, had the authority to take action against infringements of the language legislation. Private stakeholders from the Brussels Capital Region, the municipalities with facilities or the German language area may lodge a complaint with the SCLS about the language use of the administration in their relations with private individuals and the public. The Commission members may also decide themselves to deal with cases where no direct private interest is demonstrable. Within 45 days, the Joint Assembly of the SCLS must formulate an advisory opinion, possibly accompanied by an exhortation, which is served upon the plaintiff, the authorities concerned and the Minister for Home Affairs. The important change is that ever since the St. Michael's Agreement, if such an exhortation is not acted upon, the SCLS itself can take measures in order to enforce compliance with language legislation. However, this so-called subrogation power has not yet been used.

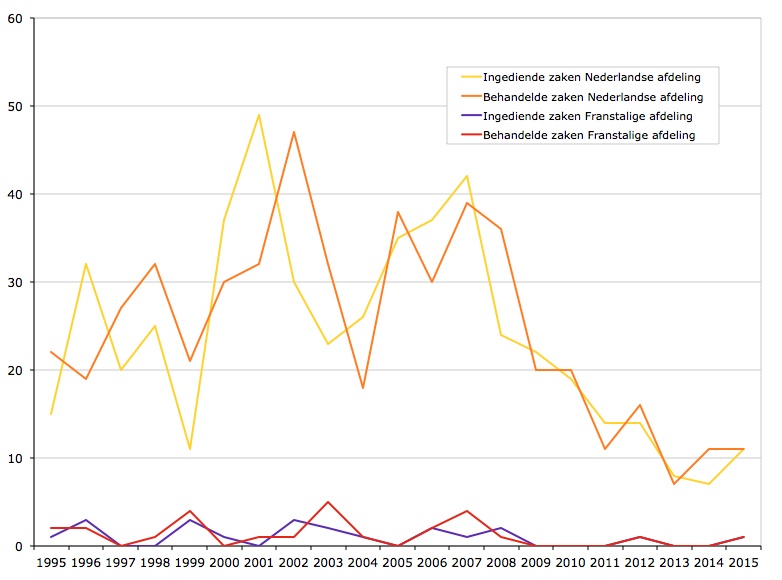

Survey of the number of cases dealt with in the period 1995-2015

The Standing Commission for Linguistic Supervision draws up an annual report about its activities and submits it to the Senate. Most cases that are filed, and therefore most advisory opinions that are issued, relate to complaints with the Joint Assembly. The requests for advisory opinions concern, among other things, the application of Dutch-French language ratios in civil service, infringements of the language legislation, the language knowledge of the staff members, multilingual brochures or inscriptions, but also the increasing number of English inscriptions (amongst others the Kiss-and-Ride signs). Different interpretations of the language legislation in the past lead to different advisory opinions from the Dutch-language and French-language divisions, but also within the respective language divisions, unanimity is not always reached. As appears from the graphs below, the Dutch-language division receives a considerably higher number of complaints and requests for advice than the French-language division. The number of requests and complaints also shows large fluctuations over the past years. Further examination of the content of the treated cases may throw some light on the impact of current events and of the relations between the Communities on the workload of the Standing Commission for Linguistic Supervision.

Graph 1: Number of cases filed with the Standing Commission, Joint Assembly, period 1995-2015

Graph 2: Number of advisory opinions issued by the Standing Commission, Joint Assembly, period 1995-2015

Graph 3: Cases filed and treated in the French-language and Dutch-language divisions of the SCLS, 1995-2015

FOOTNOTES

MORE INFORMATION

|

|

SOURCES

|

LINKS

|